On May 14th, at a registry office in Mar del Plata, 5-year-old trans boy Tito had his name and gender markers changed on his birth certificate. This was the necessary step prior to the issuing of a new Identity Card that reflects the gender he has identified with ever since he could talk.

By Sandra López Maidana for Agencia Presentes (Spanish), May 20th.

(Photos courtesy of Marcela Golfredi for La Capital/Mar del Plata)

On the coldest morning so far this fall, an unusual crowd gathered around Independencia Avenue, in Mar del Plata. There were smartly dressed couples, hurrying employees, a family and their acquaintances, neighbors, teachers, children and also a few journalists. All of them were accompanying Tito, a 5 year-old trans boy as well as his parents, Guadalupe and Matías, and his 8-year-old sister Isabella.

It was much more than mere paperwork. It was the official validation of a child’s self-perceived identity.

“He was always very shy about toys and clothing,” said his mother. “He didn’t like girl toys so he would stay with his little arms crossed. When he was a year and a half, while I was bathing him, I asked him to tilt his head back saying ‘here we go, princess’ and he babbled back ‘I’m a prince, not a princess’. I told his father and we thought he was just trying to be different from his sister. Normal child behavior. Just a phase he would move on from.”

They let some time go by. On occasions Guadalupe tried to put a dress on him. “I’m a boy,” he answered. And that was that. At home, they never imposed any restrictions on what toys and clothes he could choose.

A Challenge for Psychology

It is a rather special family, they are very open-minded. Still, they knew that outside they would not find such a welcoming environment. So they sought professional help. Along the way they encountered some therapists with varying levels of bigotry, until they ran into Jorge Visca, a psychologist with a gender approach trained in sexology. The therapist took the case as a challenge. Until then, he had accompanied the development processes of trans identities but only with adults and teenagers. Never with children. “I thought I could help this family, but it turned out I had to dismiss everything I thought I knew. It’s a very different reality from what I had studied. So I did research, educated myself, interviewed a lot of people and received clinical supervision from Valeria Pavan, the psychologist that had treated Luana, the first transgender girl. I did what psychology as a science must do in order to preserve people’s well-being.”

The task was neither simple nor standardized. “The assistance during this process is not limited to a treatment as it is often understood in psychotherapy, it’s more about accompanying. Helping patients deal with all the questions they come up with, all the body changes they can’t relate to. The identity they feel does not match the body they inhabit.”

Psychologist Jorge Visca and Lawyer Claudia Vega

This process required an interdisciplinary team that also covered the legal aspect. Jorge belongs to the Egalitarian World Association and invited Guadalupe to attend a workshop within Diana Sacayán’s Chair in Transgender Studies in the Psychology Department of the National University of Mar del Plata. There she met lawyer Claudia Vega and learned that Tito was in fact transgender.

“We assisted them with the legal part, but giving some time first to see that the child was fine. Regardless of the change in his ID, he had the right to be addressed by his chosen name, as stated in Article 12 of Law 26743 regarding Gender Identity. Any person’s gender identity must be respected whether or not they have had their gender markers changed. Tito first asked to be addressed by that name last year, he introduced himself to the other kids at kindergarten and it all went fine. It’s easy with children. His teacher last year and the institution all cooperated with his transition,” said lawyer Claudia Vega to Presentes.

Tito’s mother has started going to workshops organized by the Egalitarian World Association that deal with those parts of the Gender Identity Law that still require stronger public enforcement. But rather than perusing every article, the emphasis is placed on analyzing everyday experience. On deconstructing that which is familiar to us. “Playing with a certain toy or choosing certain clothes doesn’t make you transgender,’ says Vega. ‘Identity is not based on such little things. It’s an internal experience, something you cannot choose. That’s why it’s a transition.” Mom and dad took into consideration that Tito would be starting his last year at preschool, and he wanted to be addressed by the name on his new ID. The boy is looking forward to receiving it. His mother, Guadalupe, explained that getting the amended ID will dispense them from giving unnecessary explanations everywhere and exposing their son to violent questions as has happened in the past.

Finger-pointing

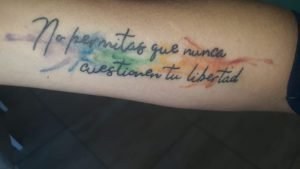

Tito doesn’t make plans for “when he grows up” but for “when he becomes a boy”, and meanwhile society points its fingers. “They say that we may have led him to be this way, but the truth is that he’s been all his life wanting to be a boy. You cannot force that on someone. Actually I didn’t want a boy, we were happy with having two girls,” said Guadalupe indirectly responding to malicious comments. Her view is summarized in a tattoo on her arm that reads “Don’t let anyone question your freedom”.

Transgender people go against society’s expectations, binarism, heteronormativity. As a result, they are subjected to violence, discrimination and pathologization. Jorge claims that “research shows that outer signs of trans identities are manifested at an early age, but since those children don’t find a supportive environment, they repress themselves and try to accommodate to what is expected. And that causes a lot of suffering. Some people mistakenly think that these children aren’t mature enough to know who they are. On the other hand, those families and institutions that accompany and protect trans children are worthy of applause. Acceptance is protection.”

For Claudia, the key is deconstruction. “Kids don’t know from birth that blue is for boys and pink is for girls. Since conception we’re already pigeonholed and stigmatized. This should make us reflect as society.”

And what if he changes his mind? The question arises from the concept of reversibility. Jorge answers: “if the person no longer feels nor manifests the same identity as before, what would be the problem with that? There are teenagers that identify themselves as non-binary. They don’t want to be pigeonholed. Gender can be fluid, it’s not something static. Anyway, there is no clinical evidence of people regretting their transition. There’s no such thing as reversibility. It doesn’t exist. Society is learning a number of things, one of which is to separate genitality from sexuality.”

Tito challenges society, beginning with his mom. “I had a little stone with his deadname carved on it. One day he said ‘your necklace says …, but my name is Tito.’ It killed me, but I kept wearing it. The day we went to change his gender markers he asked me how long I would keep that on, so I took it off.”

The day came when Guadalupe had to let go of the person she gave birth to and embrace Tito, who gave birth to himself.